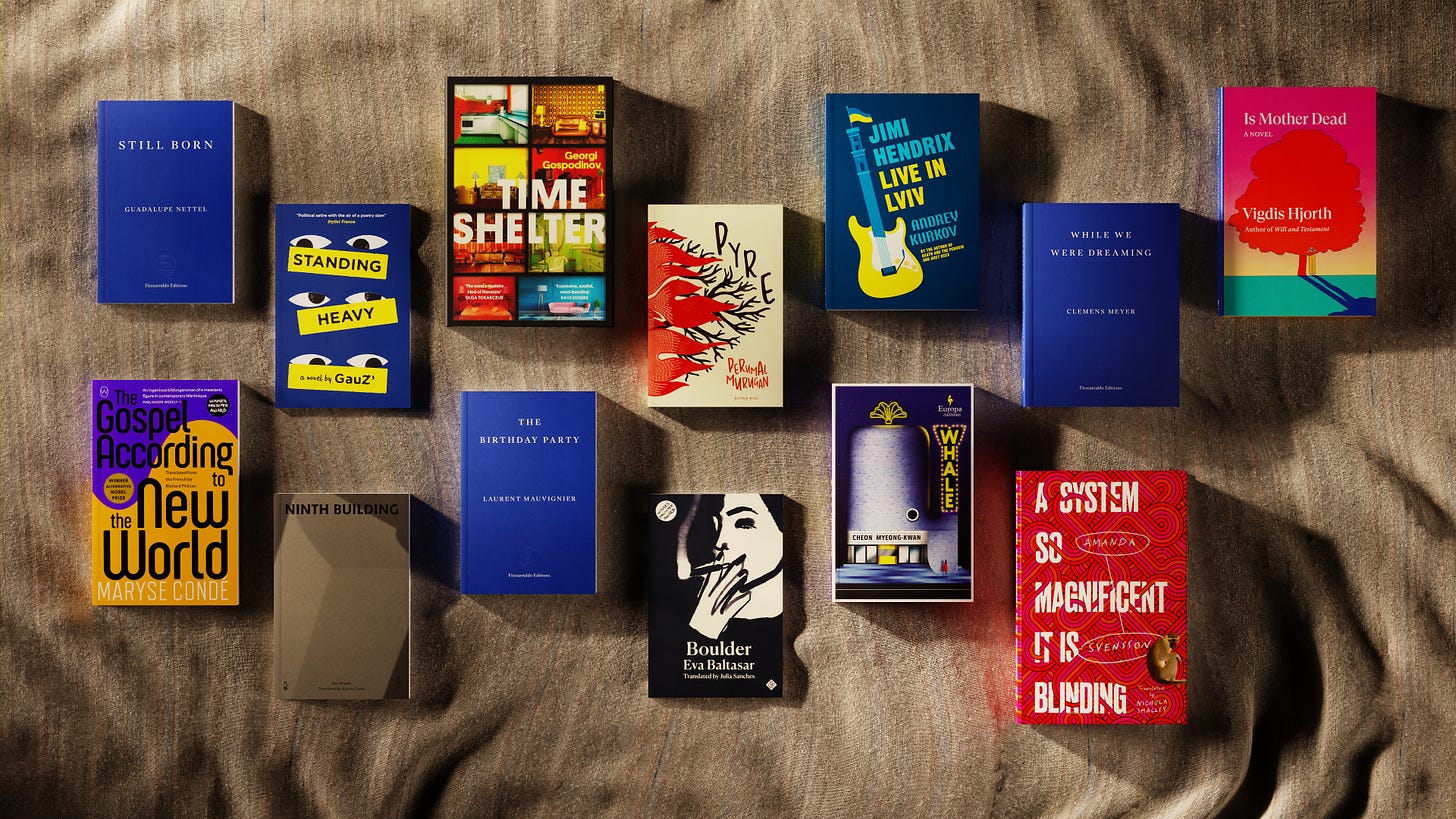

Read extracts from all 13 books on the International Booker Prize 2023 longlist

Wondering which of our longlisted titles to read first? To whet your appetite, we've selected excerpts from the opening chapter of each one

From Mexico to Sweden, Norway to South Korea, China to Guadeloupe, Côte d’Ivoire to Ukraine, join us as we explore this year’s most remarkable works of translated fiction from across the globe. Click on the link buttons below to read longer extracts on our website – and don’t forget to enter our competition to win all 13 books.

Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv by Andrey Kurkov, translated by Reuben Woolley

An affectionate portrait of one of the world’s most intriguing cities, shot through with black humour and vodka-fuelled magic realism

They stopped at an iron crucifix, which seemed to be deliberately hidden from view by the trunk of an old tree and two overgrown bushes. There were no railings here. The long-haired and mature gathering crowded around the unassuming grave. Neither first name nor surname were legible on the rusty plate affixed to the centre of the cross. One of the group squatted before it, his knees pressing into the edge of the burial mound, and pulled a plastic bag from his jacket pocket. Unfolded it. Placed a small tub of white paint down on the grass. A paintbrush appeared in his hand.

His steady hand splayed oily white letters over the plate: Jimy Hendrix 1942–1970.

Is Mother Dead by Vigdis Hjorth, translated by Charlotte Barslund

A widowed, middle-aged artist returns home to her mother's house, after decades of acrimonious absence, setting both women on edge

In the absence of information, I invent her. What is it I want to know? I wonder how she is. Not because I care about her, not in that sense, but: How have you experienced it all? How was it for you? And how do you see the situation now, the existential one which we share, what do you think about our situation? Will I never know? Will she ever know what it has been like, what it is like for me? She must wonder about it, surely? About what I think, about how I am, no matter how angry, how resentful she is, she must wonder about it because in spite of everything I am her nearly sixty year-old child.

While We Were Dreaming by Clemens Meyer, translated by Katy Derbyshire

A startlingly raw and deeply moving debut from one of Germany’s most ambitious writers

This one time, speeding through the city, wasted Fred let go of the steering wheel and said, ‘Shit, I can’t hack it no more.’ I was in the back, between Mark up to his eyeballs on drugs and Rico, still clean back then, and we couldn’t hack it either and we only had eyes for the lights of our city racing past us. And if it hadn’t been for Little Walter, who was in the front seat next to a suddenly resigned Fred, and whose life I saved twice in one night, later on (and who still just walked out on us, on another night much later), if he hadn’t grabbed the steering wheel and jumped on Fred’s lap – slumped down on the driving seat – and brought the car to a halt with a whole load of burnt rubber, I’d be dead now, or I might have lost my right arm and have to do all my paperwork left-handed.

Standing Heavy by GauZ', translated by Frank Wynne

A unique insight into everything that passes under a security guard's gaze, and a searingly witty deconstruction of colonial legacies

Every man who came into these offices unemployed leaves as a security guard. Those who already have experience in the profession know what lies in store in the coming days: spending all day standing in a shop, repeating this monotonous exercise in tedium every day, until the end of the month comes, and they are paid. Paid standing. And it is not as easy as it might seem. In order to survive in this job, to keep things in perspective, to avoid lapsing into cosy idleness or, on the contrary, fatuous zeal and bitter aggressiveness, requires either knowing how to empty your mind of every thought higher than instinct and spinal reflex or having a very engrossing inner life.

Boulder by Eva Baltasar, translated by Julia Sanches

Working as a cook on a merchant ship, a woman comes to know and love Samsa, who gives her the nickname ‘Boulder’

The days came and went, unchanging, and every night I tossed them back one swig at a time, stretched out on my narrow bed with headphones in my ears and an ashtray on my chest. I’d gone through life fixated on an intangible conviction, tied down by the handful of things that kept me from becoming penniless, an outcast. I needed to face the emptiness, an emptiness I had dreamed of so often I’d turned it into a mast, a center of gravity to hold onto when life fell to pieces around me. I’d come from nothing, polluted, and yearned for windswept lands.

Still Born by Guadalupe Nettel, translated by Rosalind Harvey

Alina and Laura are independent, career-driven women in their thirties, neither of whom have built their future around the prospect of having children

Unlike my mother’s generation, for whom it was abnormal not to have children, many women in my own age group chose to abstain. My friends, for instance, could be divided into two groups of equal size: those who considered relinquishing their freedom and sacrificing themselves for the sake of the species, and those who were prepared to accept the disgrace heaped on them by society and family as long as they could preserve their autonomy. Each one justified their position with arguments of substance. Naturally, I got along better with the second group, which included Alina.

Ninth Building by Zou Jingzhi, translated by Jeremy Tiang

A fascinating collection of vignettes based on the author’s life in China during the Cultural Revolution

The young lady looked different from six days ago. She had a scarf over her head as she mopped the workshop floor. (Later we realized someone must have shaved her head.) A piece of white cloth sewn across her chest proclaimed “Bourgeois traitor Liu Liyuan”. She still wore her face mask, and all the time she served us, kept her head lowered. In six days she’d been transformed into an ancient crone. Like before, the stove held a kettle, along with her lunchbox. A man walked in to make tea. He ordered her to remove her mask. She was motionless for a moment before plucking it off.

Pyre by Perumal Murugan, translated by Aniruddhan Vasudevan

In rural Tamil Nadu in the 1980s, young love is pitted against social discrimination

When nothing untoward happened during their journey, she wondered if her family had said good riddance to her and disowned her. Perhaps they were relieved and happy that she had not taken anything with her, that she had walked out in just the sari she was wearing. Was that all there was to it? Was that all there was to everything? Had all these years of love and affection meant nothing? Why hadn’t they come looking for her? Despite her fears of being separated from Kumaresan, she would have been somewhat comforted if someone had come after them, even if it was the police.

Time Shelter by Georgi Gospodinov, translated by Angela Rodel

A ‘clinic for the past’ offers a promising treatment for Alzheimer’s sufferers, with each floor reproducing a decade in minute detail

A certain medical professional, Dr. G. (mentioned only by initial), from a Vienna geriatric clinic in Wienerwald, a fan of the Beatles, decked out his office in the style of the ’60s. He found a Bakelite gramophone, put up posters of the band, including the famous Sgt. Pepper album cover … From the flea market he bought an old cabinet and lined it with all sorts of tchotchkes from the ’60s— soap, cigarette boxes, a set of miniature Volkswagen Beetles, Mustangs and pink Cadillacs, playbills from movies, photos of actors. The article noted that his office was piled full of old magazines, and he himself was always dressed in a turtleneck under his white coat.

The Birthday Party by Laurent Mauvignier, translated by Daniel Levin Becker

In Mauvignier's gripping tale, a nightmarish chain of events disrupts a rural hamlet’s quiet existence

No, she had wanted to live in the middle of nowhere, saying repeatedly that for her nothing was better than this nowhere, can you imagine, in the middle of nowhere, in the sticks, a place no one ever talks about and where there’s nothing to see or to do but which she loved, she said, to the point that she finally left her old life behind, the Parisian life, the art world and all the frenzy, the hysteria, the money and the parties they imagined around her life, to come and do some real work, she claimed, to grapple at last with her art in a place where she’d be left the hell alone.

A System So Magnificent It Is Blinding by Amanda Svensson, translated by Nichola Smalley

Svensson's family saga poses the question: are we free to create our own destinies or are we just part of a system beyond our control?

In 2016, Sebastian travelled to London, Clara to Easter Island, and Matilda to Västerbotten, in Northern Sweden. After that, none of them were the same. That year, their mother got an allotment in St Månslyckan. There, one frosty morning in February, she met a badger whose pungent scent and sharp claws made her think for a moment she’d come eye-to-eye with the devil, just like Luther in the Wartburg Castle. After that she started calling the allotment Fright-Delight, a name that made her feel alive. It was also the catalyst for a new-found desire to become completely pure in the eyes of the Saviour, which, over the coming months, would turn her children’s already somewhat complicated lives upside down.

Whale by Cheon Myeong-kwan, translated by Chi-Young Kim

Whale follows the lives of three linked characters in South Korea, in an adventure-satire of epic proportions

Nine days earlier, Chunhui had walked out of prison and headed south, purely on instinct. Only when she found herself by the train tracks on the outskirts of the city that housed the prison did she realize she was heading to the brickyard. She continued along the tracks. When night fell she slept against a gravestone and when she grew hungry she drank from a creek in the valley below to sate herself. Sometimes she fished out salamander eggs floating in the cold water and at others she picked mulberries along the tracks. Blisters formed on her feet and then burst, revealing tender red flesh beneath. She threw off her shoes and walked barefoot. It was taxing to walk along the tracks in the hot summer sun, but she didn’t veer away; she didn’t want to come across anyone.

The Gospel According to the New World by Maryse Condé, translated by Richard Philcox

The Gospel According to the New World takes readers on a journey in search of the origins of a miracle baby, who is rumoured to be the child of God

Everyone stood up to peer at the pram Eulalie was pushing. People were staring for a number of reasons. Firstly, Pascal was remarkably lovely. Impossible to say what race he was. But I must confess the word race is now obsolete and we should quickly replace it by another. Origin, for instance. Impossible to say what his origin was. Was he White? Was he Black? Was he Asian? Had his ancestors built the industrial cities of Europe? Did he come from the African savannah? Or from a country frozen with ice and covered in snow? He was all of that at the same time. But his beauty was not the only reason for people’s curiosity. A persistent rumor was gradually gaining ground. There was something not natural about the event.

And finally… win a set of all 13 books on the International Booker Prize 2023 longlist

In our latest competition, we’re offering the chance to win one of five bundles including all 13 longlisted titles in contention for this year’s International Booker Prize. To be in with a chance of winning, follow the link below.

Publishers across the board need to start doing exactly this — particularly at a time where there’s such a financial restriction for so many people. Libraries only have so many copies, so giving people the accessibility of a first chapter or a section to check on whether the writer is right for them — priceless.