Read our interviews with the Booker Prize 2023 longlistees

The authors in the running for this year’s prize reveal what it feels like to be nominated, their writing processes – and their favourite Booker books

In less than four weeks’ time, on Thursday September 21, we will announce the shortlist for this year’s Booker Prize. But before then, we’d like you to join us in getting to know the longlisted authors a little better.

We recently sat down with each of the 13 novelists to ask how it feels to be nominated for the world’s most influential prize for a single work of fiction, written in English and published in the UK or Ireland.

Their answers are enlightening, with each of the authors revealing the inspirations behind their work, taking us far beyond the pages of their nominated titles. You’ll find excerpts from the interviews below. Click on the links to read the full articles.

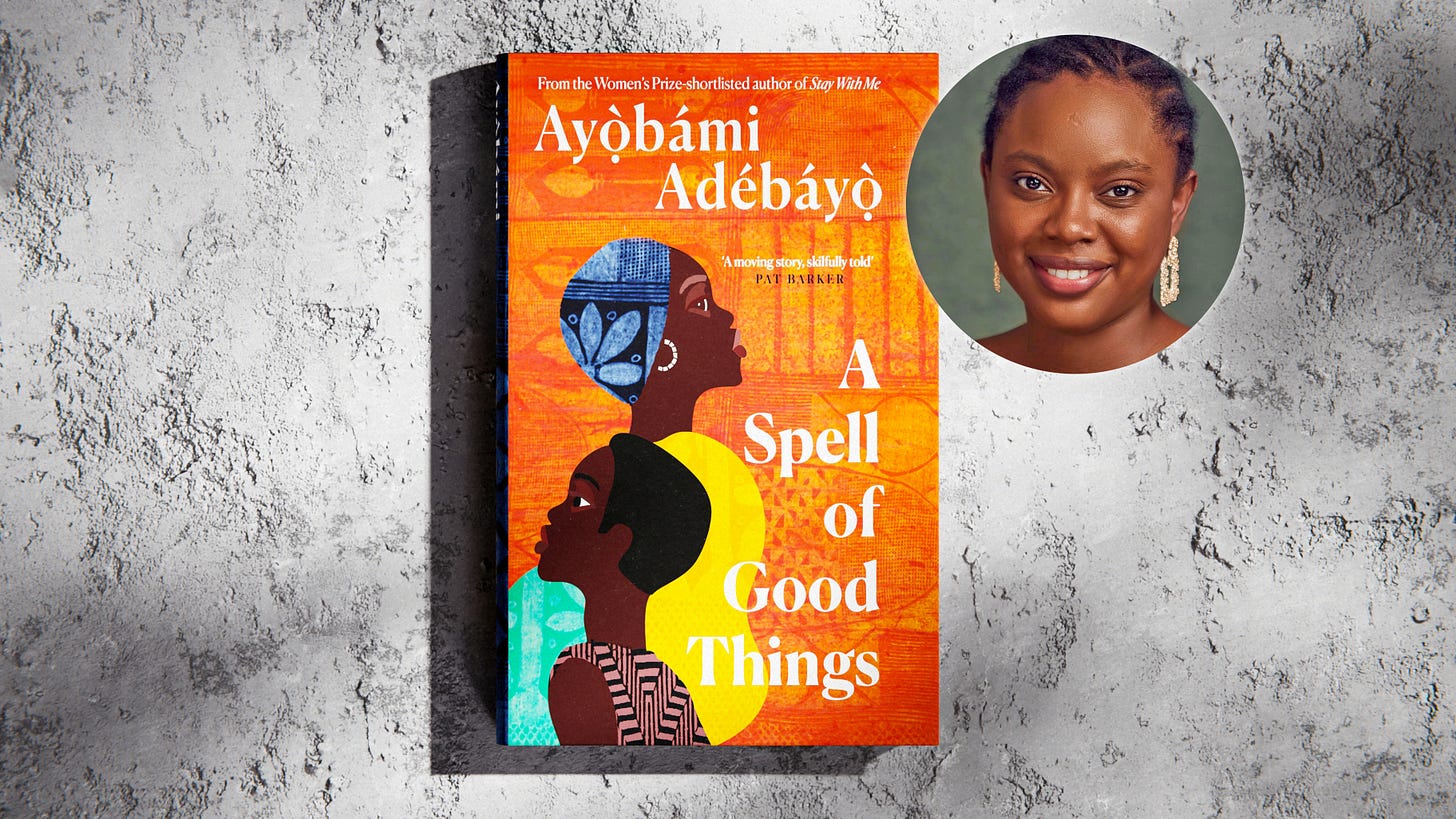

Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ, author of A Spell of Good Things

In A Spell of Good Things, you vividly illustrate a wealth and class divide in Nigerian society, with both sides undermined by abuses of power, greed and violence. What drew you to these issues as a novelist, and in writing about them was there a message you wished to impart to the reader?

‘At some point in 2012 or 2013, I was on my way home from work and there was traffic on my usual route. The bus driver then drove us through a neighbourhood I’d never been in and found almost unrecognisable. This was in the town my family had lived in since I was eight. A place I thought I knew. Yet, there I was in a neighbourhood more decrepit than I would have believed existed so close to mine. This experience informed the novel in several ways. It shaped how the story developed into a book about those who can afford to be blind to what’s in front of them and those who cannot.’

Sebastian Barry, author of Old God’s Time

Suffering and trauma – personal and collective – are often evident in your writing. What draws you to write about darker themes, and the darker side of Ireland’s history?

‘It is what seems to sit in the box of things from which I draw. It is a bit of a mystery even to me. It is where I paint, what I paint, the colours available to me. Whatever part of the brain contains all the synapses of stories and the desire to tell them, is full of these matters. But still it gives me great joy to write; as if in speaking, in telling, like a child who has been told to say nothing, I gain my own little share of freedom.’

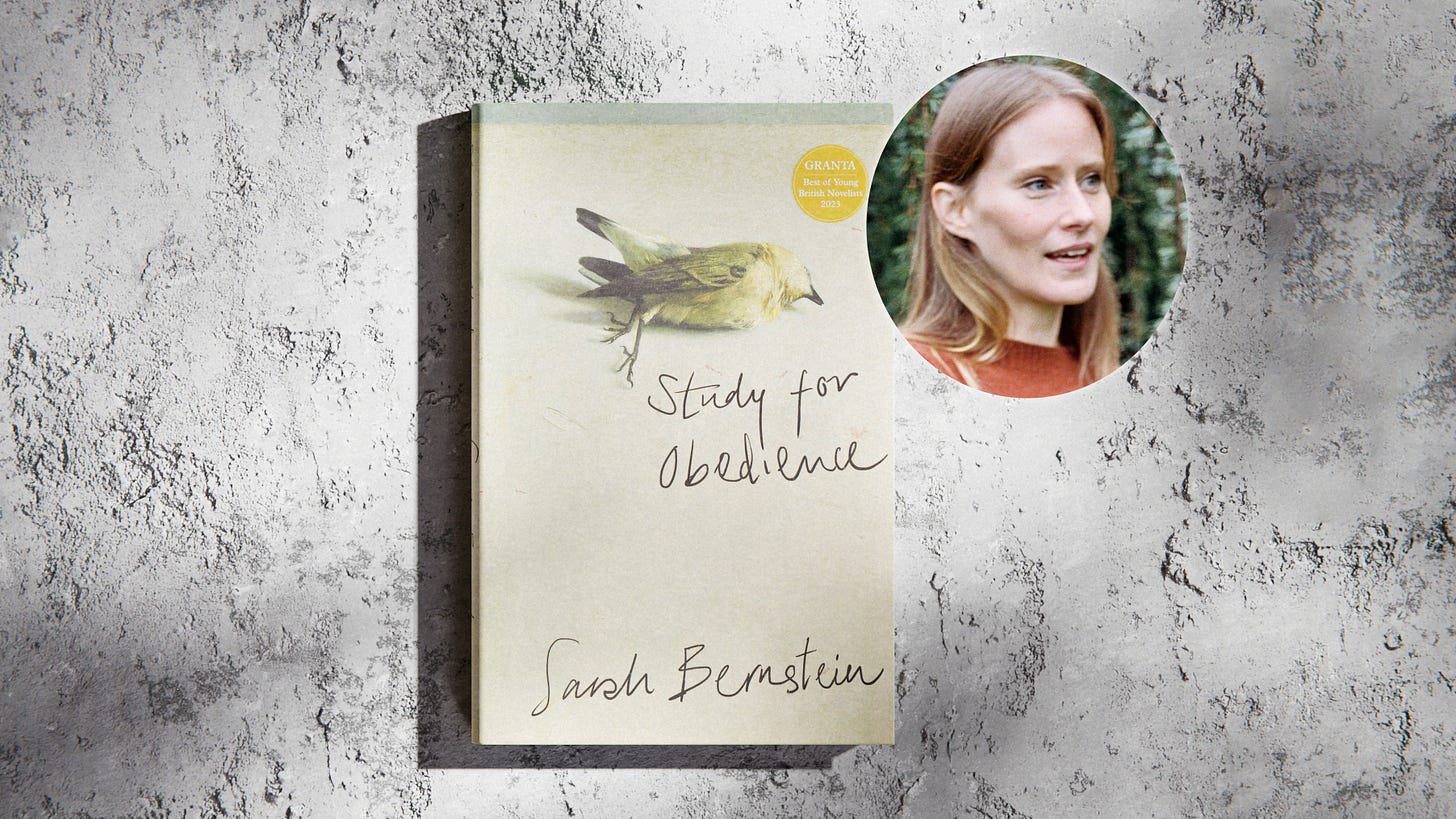

Sarah Bernstein, author of Study for Obedience

Study for Obedience contains elements of folk horror, with a palpable sense of dread and strange events occurring throughout the novel. Where do you draw your inspiration from for these discomforting images and moments?

‘Partly it comes from the countryside where I live, where there is quite a lot of sudden animal death as a matter of regular occurrence – frogs squashed on the journey from one verge to another, gulls picking off ducklings, poorly lambs never getting any better. The book tries to imagine what it might be like to be the kind of character who reads significance into what are in fact ordinary occurrences because it’s the only way she knows of making sense of what is to her an unknowable landscape. I also drew inspiration from what I’d been reading, which happened to be a lot of Shirley Jackson at the time.’

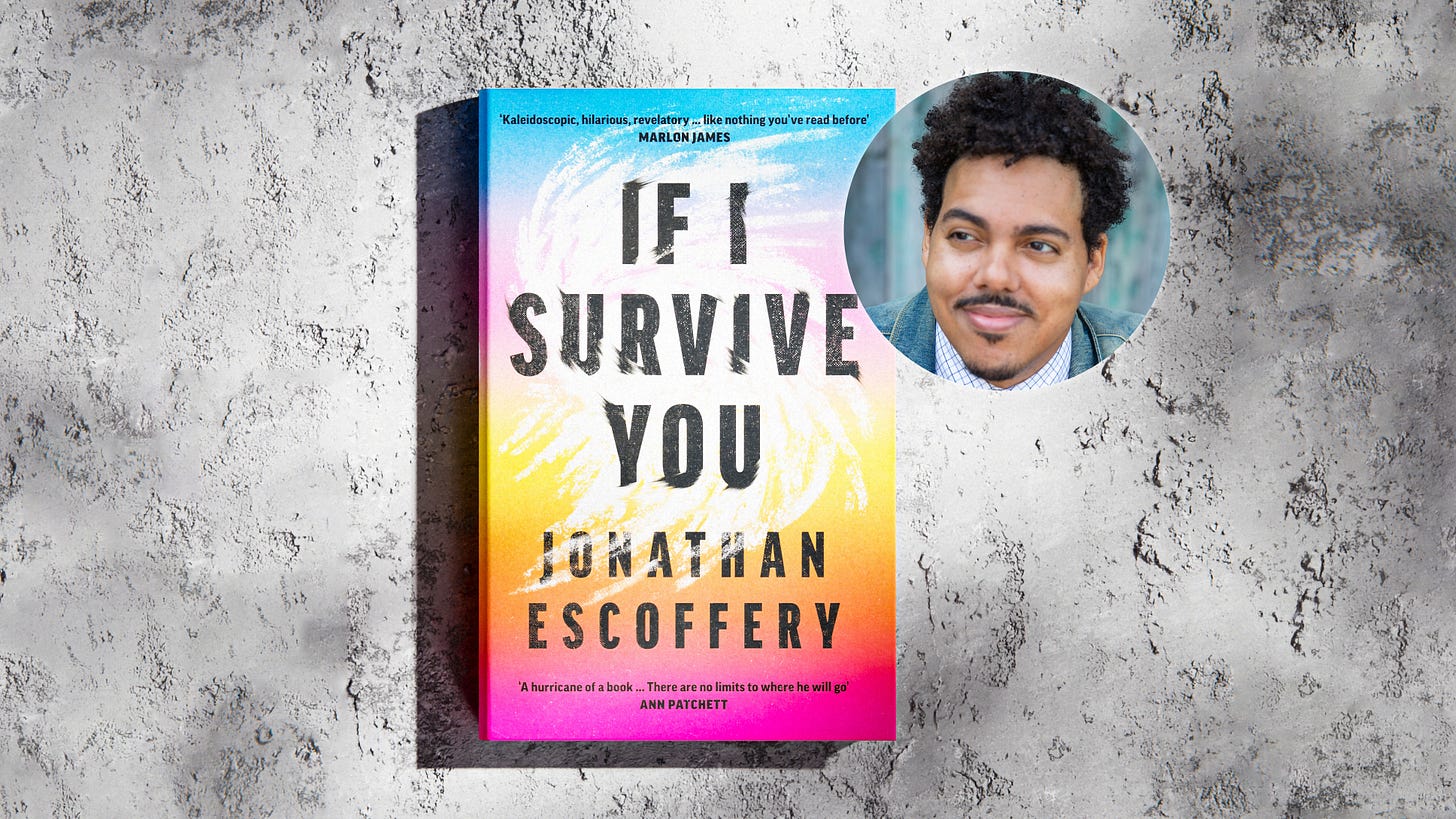

Jonathan Escoffery, author of If I Survive You

What made you want to explore the male psyche and male relationships in If I Survive You?

‘I’m interested in what models we have for being good men, and in what potentially damaging messages we send men about how to be in the world, and in how those messages get passed from one generation to the next. I also wanted to explore the question of whether fraught relationships between fathers and sons can ever be repaired, and the associated costs of attempting to repair them.’

Elaine Feeney, author of How to Build a Boat

Jamie, the 13-year-old boy at the centre of How to Build a Boat, has been described as neurodiverse by readers, yet you don’t label him within the text. As a parent of a neurodiverse child yourself, was it important that you resisted categorisation to avoid stereotypes, or ensure Jamie is not simply reduced to a condition?

‘Considering the book retrospectively, my writing impetus was parental anxiety: Can we live in an inclusive society by recognising each other, accepting one another without explanation of categorisation? Can we be tolerant? Essentially, will he be ok? It’s likely a primal concern for all parents. Therefore, the not labelling was an important consideration. I wanted the novel to speak to belonging without having to compromise who we are.’

Paul Harding, author of This Other Eden

To what extent are the characters in This Other Eden fictitious or based on real individuals? Did you always intend to stretch the boundaries of more traditional historical fiction, and where did you decide to draw the line between fact and fiction?

‘There’s a kind of continuum of “historical fiction”, ranging from, say, basically documentary narrative to mostly imagined fiction that germinated from some historical setting. The line I tried as best I could to draw between fact and fiction was the maybe couple dozen factual details that most struck me in the limited reading I did about Malaga [Island] and what they subsequently led to when I imagined my way beyond them.’

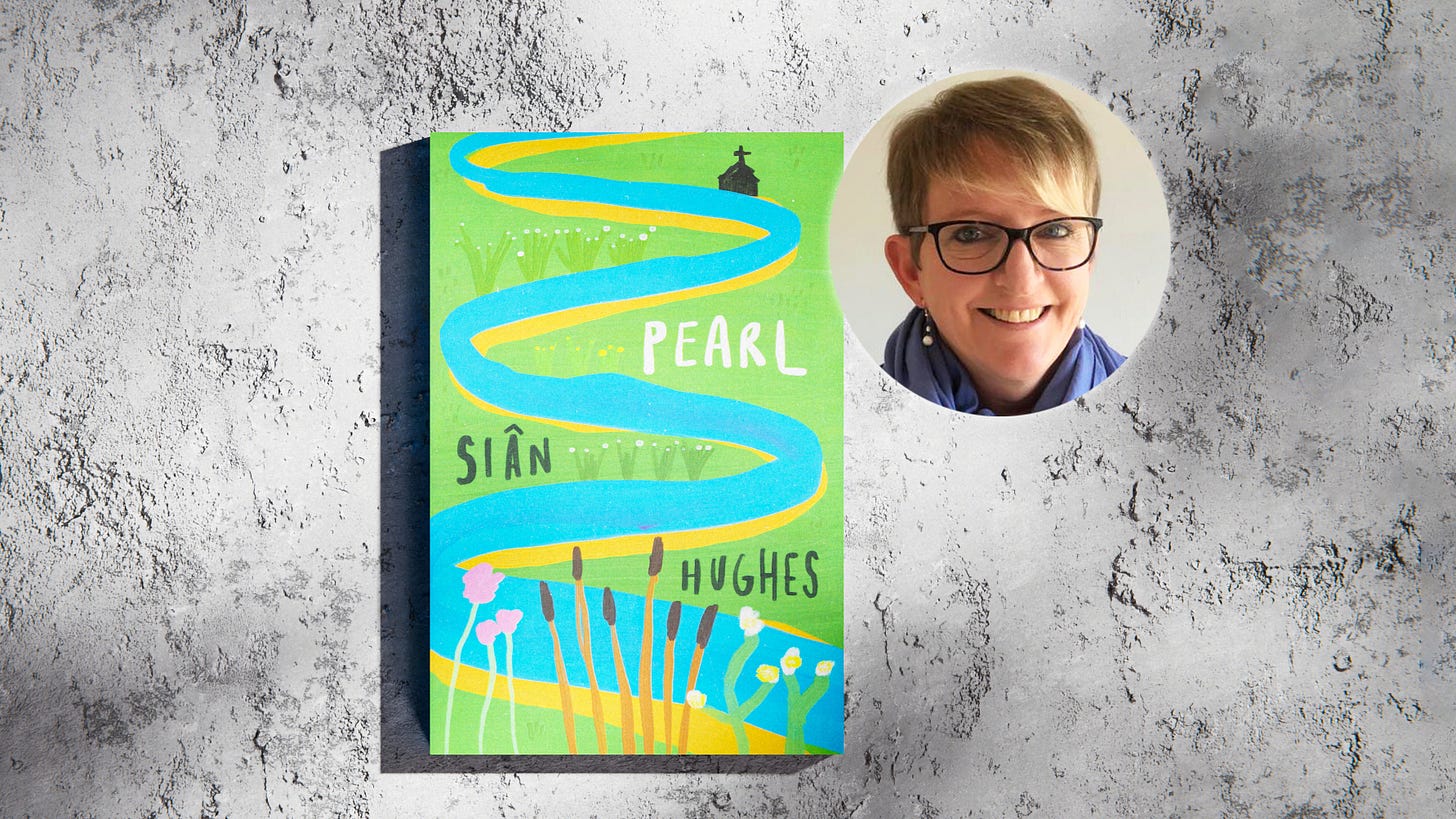

Siân Hughes, author of Pearl

How long did it take to write Pearl, and what does your writing process look like?

‘Okay, well this is embarrassing. I first invented the characters as a teenager, then I became obsessed with the Medieval poem “Pearl” and with trying to write about the death by drowning of a good friend. I wrote the entire book in long-hand first. Or the first version. I have written more versions – all totally different with different narrators and with timelines varying from 24 hours to 32 years – than I am going to admit. All I can say is, I don’t exactly recommend this method of lifelong obsession, but this was the project that would not leave me alone.’

Viktoria Lloyd-Barlow, author of All the Little Bird-Hearts

One of the many stereotypes surrounding autism is that autistic people are more drawn to STEM subjects than art or creative writing. To what extent do you think your own work might help change those perceptions, or open doors for other autistic writers of fiction?

‘I hope that some of the joys of the condition, as well as the challenges, are evident to readers of my book. And I hope too, that other autistic writers might read my work and find it authentic, even if it does not directly reflect their own experiences. There are many autistic writers producing good work and I would be happy both to be included in this number and to see more autistic writing being celebrated.’

Paul Lynch, author of Prophet Song

Prophet Song presents a dystopian Ireland, depicting a government descending into tyranny. What inspired you to base the novel in your home country, and was it inspired by any real-world events?

‘I was trying to see into the modern chaos. The unrest in Western democracies. The problem of Syria – the implosion of an entire nation, the scale of its refugee crisis and the West’s indifference. The invasion of Ukraine had not even begun. I couldn’t write directly about Syria so I brought the problem to Ireland as a simulation.’

Martin MacInnes, author of In Ascension

In Ascension contains elements of science fiction, but is it fair or accurate to call it a sci-fi novel?

‘I’m happy to call In Ascension SF, even if it risks disappointing some readers who might bring narrower expectations to the genre. I see it as an unlimited genre, a platform for going anywhere. An SF novel can be as high-brow as any other genre, can have strong characters and be filled with beautiful writing. I’ve heard people say that they don’t read science fiction, but they read this, and I’m torn about that – I’m obviously happy if they’re reading me, but it’s a pity they thought SF was only one thing.’

Chetna Maroo, author of Western Lane

What made you choose sport – and squash in particular – as a way for the family in Western Lane to deal with their grief?

‘As I began writing, it made sense to me – the way attention is focused outwards in the game, the concentration, the movement of bodies in sync with one another. There was also something about the squash court itself, about the simple white box: it’s such a surreal, unfamiliar place, and in part because of the unfamiliarity it’s a place where time seems suspended and the outside world can be forgotten.’

Paul Murray, author of The Bee Sting

The Bee Sting has been described as ‘a novel about the past and our inability to ever outrun it’ – which could possibly be said of several other novels on this year’s longlist, many of which concern families navigating some sort of trauma. Is that how you would sum it up? If not, how else?

‘That’s a pretty good description. Faulkner again has this fantastic line, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Time, the persistence of the past, these are things the novel as a form is very good at. That said, I really wanted to write about the present moment. Most of the book is set in the present, with all of its attendant terrors – the rise of fascism, the pornification of reality, the subordination of embodied experience to representations and so on. More than anything, I wanted to write about climate change. That sense of impending doom is something that feels different to the nuclear threat, for example, and gives a tone to the present that is new.’

Tan Twan Eng, author of The House of Doors

The House of Doors is set during Britain’s colonial rule of Malaya, and your other novels have been located in the early or mid-20th century. What is it about that time period that interests you?

‘The dynamics of power of that period: between men and women, between the ruler and the ruled, between people of different races and cultures. I’m fascinated by how East and West clashed, merged, pulled apart; how they enriched but also damaged each other. Sadly, all these issues are still very relevant today. We did not know very much about one another then, and I feel we still don’t today.’

Which books from the longlist have you read, and loved, so far? What are your predictions for the shortlist? Let us know in the comments below.

Loved both House of Doors and Old God's Time.

Loved both Adebayo’s and Tan Twan’s. Thank you.